The promise of lenacapavir

The Food and Drug Administration just approved a revolutionary new HIV prevention tool, but the Trump administration could undermine this breakthrough

Today marks a milestone in HIV prevention. Don’t expect a lot of celebrating.

The Food and Drug Administration has authorized a new HIV prevention tool: lenacapavir. When given twice a year as an injection, the anti-retroviral is almost completely effective at preventing HIV infection.

In one study, presented at last year’s International AIDS Conference in Munich, there was not a single HIV infection among the 2,134 women who received lenacapavir. These results were so astonishing that the thousands of researchers attending an otherwise-sleepy early morning plenary stood up and applauded.

FDA approval is a crucial step in facilitating broader access to this prevention method. It means Americans, who are always at the front of the line, can start using the shot almost immediately. The vast majority of the 1.3 million people infected with HIV each year, of course, are not in the United States. But FDA approval could signal that regulators in the low- and middle-income countries where they actually live should speed up adoption.

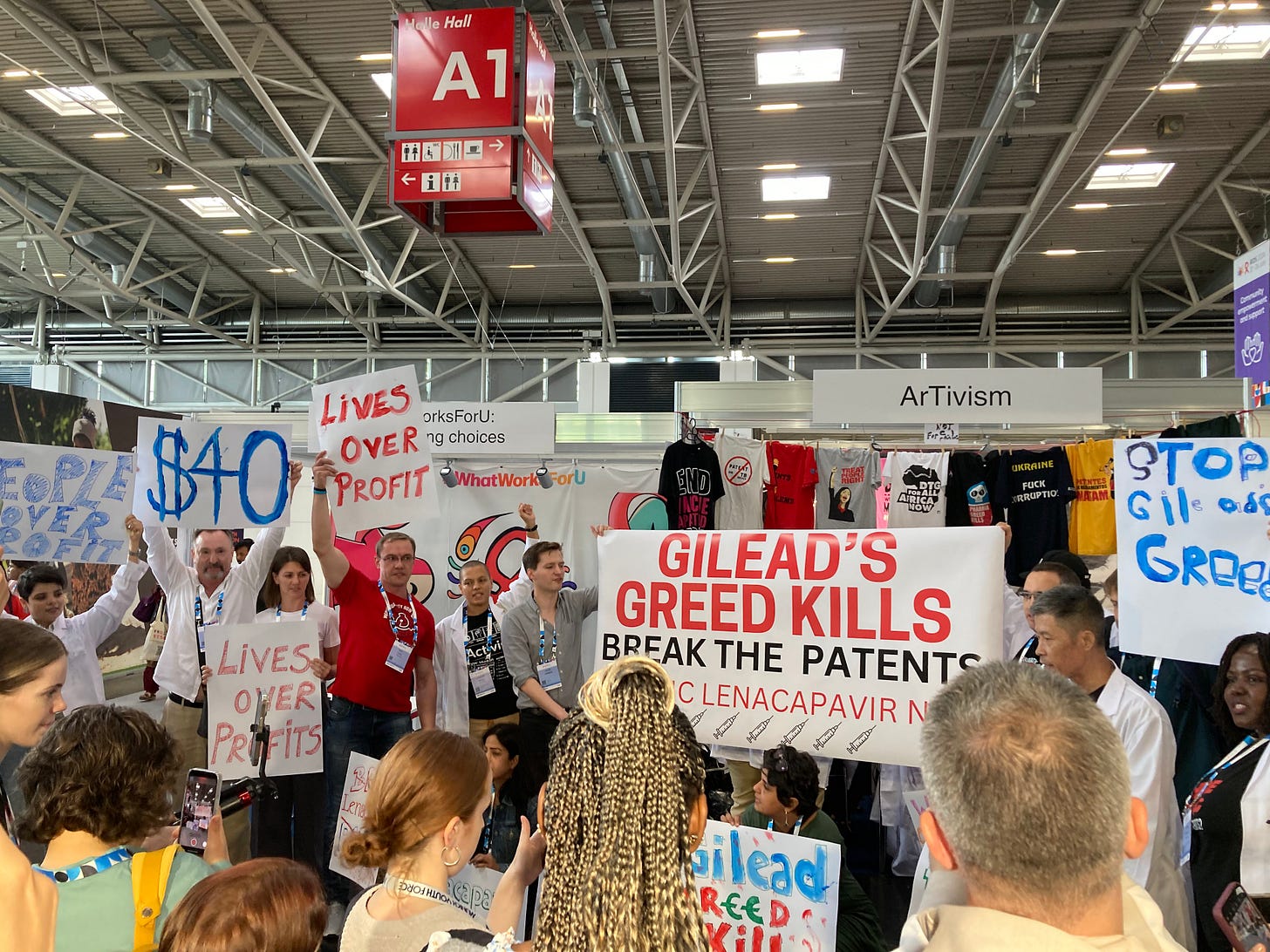

The problem is twofold. First, lenacapavir is expensive. Gilead, the company that manufactures it, is probably going to charge $25,000 per person per year in the United States. The price will be significantly lower in poorer countries, but still not low enough for lenacapavir to be made as widely available as it needs to be.

We knew this already. Officials had a plan to pay that higher price for now, while working to quickly make lenacapavir more affordable. Then Donald Trump came into office and effectively withdrew U.S. support for HIV prevention. Before Trump, the United States paid for 90 percent of the people who started on some form of anti-retroviral medicine in order to stop themselves from becoming infected, a method known as pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP.

Now it appears the carefully constructed strategies to accelerate access to lenacapavir could be scuttled and the most promising prevention method ever developed could be wasted.

---

Lenacapavir is, as experts have repeatedly told me, the closest we are going to get to an HIV vaccine in a while. (Particularly after the Trump administration drastically curtailed HIV vaccine research, including a crucial $258 million program.)

Its form is central to lenacapavir’s effectiveness.

The most common – and cheapest – form of PrEP is a pill that must be taken daily. I talk regularly to people who dislike it, though.

There is the burden of a daily pill, of course. But using oral PrEP can complicate relationships. Oliver, a young Ugandan, started PrEP because she does not trust her boyfriend not to cheat on her. She has also turned to sex work because it is the only way she can figure out how to survive. She does not want him to know either of these things. But the pills are hard to hide. And it was difficult to explain why she was taking PrEP when he discovered it.

The beauty of lenacapavir or other injectable forms of PrEP is that no one else has to know you’re on it, except the person administering the shot.

Oliver is desperate for access to lenacapavir. Even though it is not yet available in Uganda, she knows all about it. Ugandan women volunteered to be part of the very studies that just convinced the FDA to approve the method. They put their bodies at risk to advance science. Word spread quickly about the miracle method.

As the promise of lenacapavir became apparent, U.S. leaders began to spearhead efforts to ensure the tool would quickly reach the communities that would benefit from it the most. This means young girls and adolescent women in sub-Saharan Africa, who are at heightened risk of HIV infection, but whose access to PrEP is limited. Also the poor and marginalized communities, including sex workers, who regularly move and cannot always manage to hang on to a tin of oral PrEP.

Through the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, or PEPFAR, the U.S. government had promised to speed access to lenacapavir for two million people over three years.

As I have written elsewhere, this is short of what is needed.

Lenacapavir is not a vaccine. It still requires two shots a year. And it must reach a lot of people. To prevent a single HIV infection, one researcher told me an estimated 50 people must be on PrEP. To prevent the 1.3 million new infections that are happening each year, then, would mean getting tens of millions of people on lenacapavir or some other form of PrEP.

But two million was a start, particularly since Gilead is almost certainly setting a price for lenacapavir well above what oral PrEP manufacturers are charging. (South Africa pays $40 per patient per year for oral PrEP, for instance, while researchers estimate that Gilead is planning to charge as much as $200 for a year’s supply of lenacapavir.)

The funding commitment was a vote of confidence in the method’s potential. And it also promised a market to the six generic manufacturers that Gilead is allowing to produce lenacapavir. Their versions could be available within two years. The PEPFAR purchase demonstrated that there is a pool of money available to pay for lenacapavir. A pool the manufacturers could eventually access, if they set a competitive price.

Indeed, some researchers have estimated that generic companies would be able to produce a version of lenacapavir for as little as $25 per person per year, if they could reach a big enough scale. There was a path to generic lenacapavir that is actually cheaper than oral PrEP.

Then PEPFAR – and the U.S. government – walked away from prevention, threatening to undermine the whole strategy.

The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria was PEPFAR’s partner in this project. And its officials maintain their commitment to providing the two million doses. But the Global Fund lacks PEPFAR’s resources and, alone, does not offer the same financial assurance.

Already one Ugandan researcher told me that additional trials of lenacapavir have been delayed. There was an idea was that these could serve as a precursor to a larger national program. But with no guarantee that the funds will be available to support a country-wide rollout, the trials are at risk of disappearing.

The promise of lenacapavir is at risk of disappearing.

---

This is not hyperbole. It has happened before.

Before there was lenacapavir, there was cabotegravir, or CAB-LA. CAB-LA is also an injectable form of prevention, although it must be administered every two months. It received FDA approval back in December 2021.

More than four years later, it is still not widely available across most low- and middle-income countries.

It’s manufacturer, Viiv, also set prices well above the cost of oral PrEP. In this instance, though, donors, including PEPFAR were reluctant to pay. Generic production has been slow to develop, at least in part because there was no guarantee of a market.

The drug has been approved in many places for distribution, but if a client prefers CAB-LA, they must pay for it out of pocket. Without support from the government or donors, the price is proving much too steep.

In May, I visited the Pribta Tangerine Clinic in Bangkok, which tailors its services to transgender clients and other members of the LGBTQI+ community. The clinic started offering CAB-LA earlier this year at a price of more than $450. It’s the cheapest they can afford to make it available, but it’s proven far too expensive for most of their clients.

“Oral PrEP remains more popular,” Onaroon Surisarn, a nurse at the clinic, told me.

At least Tangerine’s wealthier clients have a choice. In Uganda, where research on CAB-LA was conducted, people can still only access the method through ongoing trials.

Oliver was one of them. She would have preferred the six-month injectable, but she was happy with any long-acting PrEP. She got started on CAB-LA earlier this year through an implementation trial. But the study was forced to close after Trump cut off nearly all U.S. funding for HIV prevention. So now Oliver doesn’t even have access to CAB-LA.

“How am I going to protect my life as they are now going to stop?” she wants to know. “I have to go back to work. The injection is not there.” Oral PrEP is the only option available to her, which feels unfair since she knows better choices are out there.

The rollout of lenacapavir was supposed to be informed by what happened with CAB-LA. Generic manufacturers were introduced early and PEPFAR and other donors made their commitment explicit. Oliver and anyone else who would prefer a long-acting injectable were not supposed to have to wait years after FDA approval to get access.

All of those carefully laid plans are now in jeopardy, though, as Washington threatens to walk away from the lessons of the past and from lenacapavir.