A tale of two districts

The U.S. government says it has restored funding for basic HIV services globally. Ugandans are finding that access to those services really depends on Elon Musk.

One of the more perverse aspects of the Trump administration’s cuts to global HIV support is the vast discrepancies in services they have created within countries. In Uganda, access to HIV treatment now depends on what district you call home.

A quick background: The U.S. government, through the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, has spent more than $5 billion on Uganda’s HIV response since it launched in 2003. For reasons too tedious to get into, that money has been channeled through two U.S. organizations: the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the U.S. Agency for International Development.

The two agencies basically carved up the country geographically, so Ugandans live either in CDC sub-regions or USAID sub-regions. The agencies then added to that patchwork by hiring non-governmental organizations to run services within smaller subdivisions, like districts. And Uganda is awash in districts. One of President Yoweri Museveni’s tricks to staying in power for 39 years has been to carve out districts and then dole out the new leadership jobs in return for political loyalty.

When the Trump administration halted all U.S. aid on January 24, that included all HIV programs in all of Uganda’s districts. Then Secretary of State Marco Rubio started exempting some services from the funding freeze. He eventually got around to issuing a waiver that allowed for the ongoing delivery of HIV treatment and of services that help stop mothers from transmitting HIV to their children, a process known as PMTCT.

Except a trip across Uganda reveals that those exemptions are still inconsistently applied more than two months after they were issued. Despite Rubio’s promise, it is Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency that determines what Ugandans still benefit from HIV services.

Kamuli District

Kamuli is the dominion of Rebecca Kadaga, the former speaker of Uganda’s parliament. The eastern region’s fortunes have long been tied to hers, and with Kadaga currently politically sidelined, Kamuli also has the feeling of an area in decline.

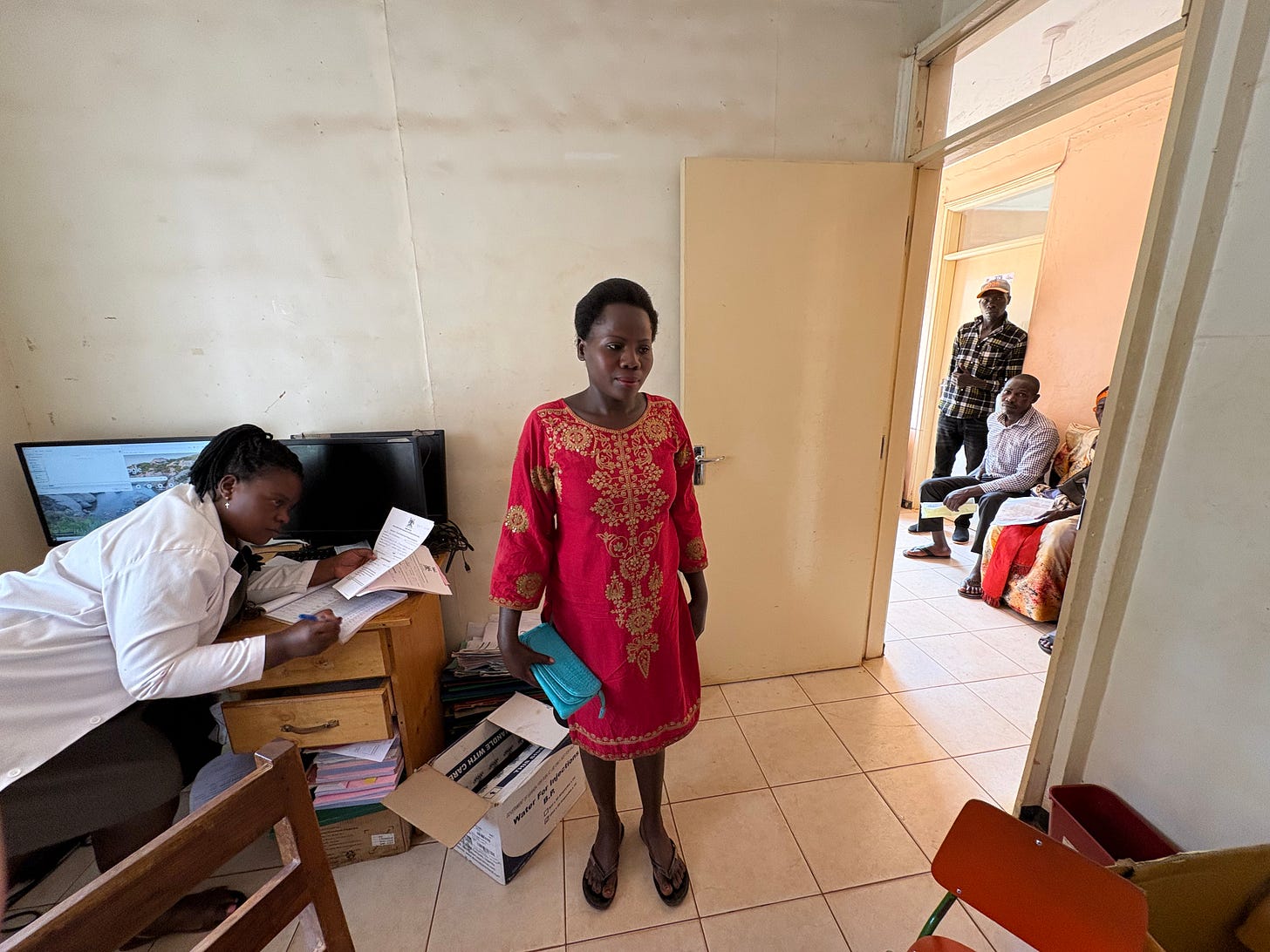

That extends to the Kamuli General Hospital, a dark, labyrinthine structure, with an HIV clinic tucked into one recess. The waiting room is packed on a Monday afternoon. This is a direct result of the confusion Rubio and Musk have introduced.

Joweria Kasiir, a short, stern woman, runs the clinic. She is one of only two Ugandan government employees. The rest of the staff – the people who organized files, who followed up with clients that weren’t coming to get their refills and who reached out to the community to encourage them to get tested – were paid for by USAID through one of those NGOs. In this case, it was the Makerere University Joint AIDS Program, or MJAP.

Except DOGE has ruthlessly dismantled USAID over the past three months. The vast majority of its employees have been fired and its contracts cancelled. Those that escaped the massacre have been put under the direct purview of Rubio’s State Department. MJAP’s work through USAID has not been spared.

Beginning in late January, the U.S. government has frozen MJAP’s services, then exempted them, then canceled the program’s contract before ultimately rescinding that cancellation exclusively for treatment and PMTCT.

Except with USAID now dissolved, MJAP’s administrators seem unclear who they actually report to. And the MJAP employees who worked at Kamuli General Hospital are uncertain whether they even have jobs. They have been told to report to work, but it has been months since they received any salary. After all the whipsawing about, it’s understandable that many have stopped showing up.

That leaves Kasiir to struggle, essentially single-handedly, to sustain basic services at the HIV clinic. With 3,000 people on treatment, she now sees patients without interruption from 8:30 every morning until the waiting room is empty.

“As long as the drugs are there, for us, we are there as health workers,” she tells me. “Some other facilities stopped working, even when the stock is there. But now, for me, I continue services. We are just stubbornly moving.”

Without MJAP’s support, though, what she can provide is well short of what Rubio guaranteed with his waiver. Treatment and PMTCT are still available, but only for those people who can afford to reach the clinic and then spend hours waiting. She can no longer run the tests to make sure the treatment is actually working. And with her drug supplies dwindling, she is afraid to take on clients from less functional facilities.

That includes a smaller health center I visited outside Kamuli, which supports 360 people living with HIV. It was out of four different forms of treatment when I visited last week. Some had been out of stock for more than six weeks by the time I visited. The center doesn’t even have condoms to distribute to people looking to protect themselves from infection.

“If these people who are already on the medication are not able to receive, they are going to continue spreading. If the medications that are supposed to be used for prevention are not there, we are unable to prevent,” Geofrey Mberenye, the head of the treatment clinic, explains to me. “It’s still confusion. We don’t have clear information. We don’t know. We’re not sure who is supposed to deliver the communication.”

Kiboga District

It is only by happenstance that Kiboga General Hospital does not share the same fate as Kamuli’s. Kiboga is 148 miles northeast of Kamuli, a nondescript district nestled in a region of lush, rolling hills. The hospital is one of the few landmarks of note in Kiboga town. It’s a sprawling, airy facility whose design dates back to Milton Obote’s first term as president in the late 1960s.

The HIV clinic in Kiboga General Hospital was humming on a recent Tuesday. That’s because the PEPFAR implementing partners for Kiboga get their funding from CDC, not USAID.

“I would not talk of any gap,” Gabriel Watuwa, the taciturn HIV focal person for Kiboga District, tells me. That’s because after Rubio issued his waiver, “everyone was brought back to work. So work resumed normally.” Well, almost normally. A few of the programs to reach out to the community have been suspended. And CDC-funded programs are also not supposed to deliver U.S.-funded medicine for prevention to anyone except HIV-positive women who risk transmitting the virus to their babies.

But because CDC is still supporting basic services, that has given government-funded employees the space to develop workarounds to these restrictions. So treatment and prevention are still reaching the people who need it, regardless of whether they can make it to a government facility.

It is not the seamless process that existed before Trump took office, but it is a level of coverage that is inconceivable for Kasiir, back in Kamuli.

Kamuli suffers for the absurd reason that USAID fell in DOGE’s crosshairs early. Kiboga is spared because the CDC went relatively unnoticed for the first few months of Trump’s term. No matter what Rubio has claimed, the Musk’s DOGE has no real concern for preserving a base level of HIV services.

In the districts that still have services, people recognize their luck. And they live with the constant anxiety that it will soon run it.

“Ever since Trump came with this stop-work order, I have had the fear that the medicine will be empty from the health facility,” Florence Namyanje tells me. A short, sweet-natured woman, Namyanje has been on treatment since she was diagnosed with HIV in 2012. Her drugs and support have always been funded by PEPFAR.

Though Namyanje was able to get her usual refill of her treatment when she visited Kiboga General Hospital this time, she is not convinced that will be the case when she returns in three months. She could be right.

The CDC-supported sub-regions in Uganda may soon suffer the same deprivations as their USAID counterparts.

Last week DOGE orchestrated the firing of hundreds of CDC employees, including much of the department responsible for administering PEPFAR programs in Uganda. It’s likely Kiboga will soon experience the same shortages as Kamuli.

At least last week, though, Namyanje was glad she lived in Kiboga.

Again this shows the randomness of who gets help and who doesn’t with the arbitrary nature of this administration. For a nation that is dedicated to justice this is wrong. I’m sure the economic instability that has hit the world this week is making the situation worse.